Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 01/25/2019 in all areas

-

I'm of the controversial opinion — and I'll die on this hill — that the arts, western music included, have long since reached their highest possible standards. I will argue that paintings by the likes of Michelangelo and Da Vinci, sculptures such as David or The Rape of Persephone, western classical, baroque, romantic, folk, etc. music, and so on were and remain the best examples of their respective mediums. They exemplify the mastery over their respective crafts that one ought to aspire to. And this is obvious in the fact that these works continue to stand the test of time as being considered the all-time greats. They still have this appeal to people, hundreds of years later. Here's the thing about reaching a high standard: The only way to truly be "original" from there is to do something that defies this standard, and the inevitable result of abandoning that paradigm is a lower standard. In the contemporary sense regarding film music, John Williams, Goldsmith, Silvestri, Korngold, etc. are still seen as the gold standard. Their music for Star Wars, Back To The Future, whatever...they're the most popular orchestral pieces of the 20th and so far 21st centuries. Why? Because they are reminiscent of, and in many cases directly lift from the standards established in the romantic era and before. "Batman Begins" or the scores to most of the Marvel movies, are absolutely NOT of that standard. They work for what they are, but what they are is vapid, empty pieces of music to accompany vapid, empty films. The only piece most people can recall any melody from in the entire franchise, is the "Avenger's Theme"...composed by Alan Silvestri. These kinds of works, will — and I'll argue already have — fallen by the wayside if not be forgotten entirely in time. The MCU, much like the band KISS, will be remembered more for their record-breaking sales and furthering of unabashed consumerism of the day than any actual artistic or cultural worth. So what to do about originality? Concern yourself with living up the high standards of yore rather than being unique. The obsession with being "unique" is actually a lie anyway, one which is symptomatic of society's post-enlightenment shift away from seeking to cultivate virtue and wisdom by understanding what we ought to love. It's fine to love trailer music, but you ought to love the works of Mozart or John Williams more. Otherwise, what you wind up doing is trying to convince everyone else to conform to the idea that your music of a lower standard, is actually just as good as any of the greats because you feel there is no inherent meaning in anything other than that which we choose to impart on it. So I agree with Coleridge about the waterfall: The waterfall is, and has to be sublime — not just "pretty".2 points

-

You embody the exact kind of neurosis, materialism and projection that I, Monarcheon, and the OP have all referred to. Just because you cannot recognize or do not want to put in the effort to live up to a standard of quality does not make whatever you want to substitute it with just as good. "Different" doesn't matter when different sucks compared to the standard. This Is not simply a "discount version" of this Rather, they are both works of a similarly high standard. And while this May be "different", it is definitely not as good, and the sculptor nowhere near as skilled as the previous examples.1 point

-

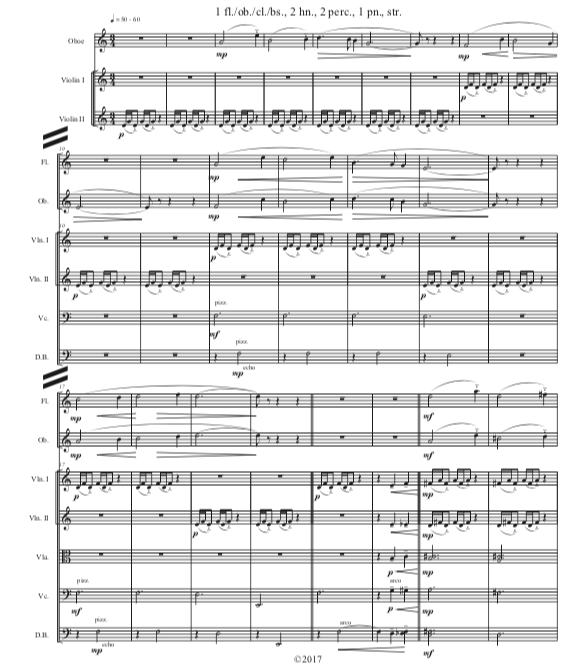

In a lot of scores, there is actually just 3 full pages of rests for those instruments that happen to not play. I know many conductors who prefer this visual score style as opposed to the alternative, where instruments that don't play are simply removed from the pages that don't include them (excluding the first page – the example below is a bad one of this). Two slashes are used to indicate a break in the system if only few enough instruments play to warrant a page break.1 point

-

@Theodore Servin I finally got a chance to listen to the Ivanov piece, and what a gem it is! And how about that incredible A below the bass staff in the basses at the end? That's the open A string on a double-bass, just a fourth higher than its lowest (regular) note! I didn't even think that was humanly possible! My little brother is a basso profundo like that...he can easily hit low-C, but I've never heard anything like this. One of the most impressive things about the piece to me as a technician is the fact that Sheremetev, blatantly and obviously with purpose, commits parallel octaves between the 1st Tenor and 2nd Bass at the climax of the piece (after that excruciating long crescendo), going from what I believe is a root-position A-flat major chord to a 2nd-Inversion C major chord, and he totally gets a free pass from me, even though he might have avoided them by changing either part just a little! Despite being totally illicit by Western standards, it's one of the most electrifying moments in the repertoire to my ears just as is, and I wouldn't change it for the world. I don't know for sure, but having heard other anomalies of that kind, I have a feeling that the rules of harmony don't always necessarily apply as strictly to Russian choral music, and that's fine as long as the results are so eminently worth it. Heartily agreed. By now, you might have surmised that we definitely share an enthusiasm for underrated composers!1 point

-

This is an interesting scenario. I've done both things (written for specific people, and written stuff without anyone in mind,) and I think that the most important thing is that if you're writing for specific people, they should know and you should tell them what you're doing to some degree. You should be very familiar with what repertoire they can play well and what's their overall technical level. I've had mostly good experiences with this as people I've written things for trust me enough to let me do whatever I want, and it's worked out pretty well. However, you can't count on that being the case and it could as well be that they can put restrictions on what they want you to write, etc etc. If it's an outright paid commission, then sure it doesn't matter that much that you cater to their wishes since a job's a job, but in my experience I've always done things in a way where I have the freedom I need to do my thing first and foremost. However, I understand that may not be always possible or reasonable. The best way to go about it, in my opinion, is to write for no specific person and write what you actually just want to hear. Then, after you've written the piece, see if there are any comments on possible changes or interpretations that you may be willing to compromise on. I think this gives off the best impression of you as composer since you are sure of your work but at the same time you are open for suggestions, just remember that you are the boss in the end, with all the responsibility that entails.1 point

-

There is a time-honoured tradition of this, especially in the days of court orchestras. Haydn, for example, had an orchestra of virtuosi at his disposal for Prince Esterházy's entertainment, and he often made special use of individual players' strengths, especially earlier in his career. When writing specifically for his patron the Prince, who played a bizarre, now-extinct instrument called the baryton, he was careful to give the Prince interesting things to play while staying within his limited technical abilities. When he went to London, he was also well aware of the fine orchestra he was going to be writing for, and his final 12 symphonies show it. When writing for a specific ensemble, I almost always take into consideration what I know to be their strengths, and almost more importantly, their weaknesses. For example, when writing my Missa Brevis 4 vocibus (posted here), the commissioner advised me that his soprano section wasn't really capable of singing above F at the top of the treble staff, hence I only once wrote a G for them (having no other choice in that spot), but otherwise kept the range of the soprano part capped at F. Though it was limiting, had I not done so, it would have caused problems for the very people who were paying me for the composition. However, he had a stellar tenor section, including himself (and I knew his fine voice well), so I several times took the tenors up to A above the staff, and they performed admirably. When not writing with a specific ensemble in mind, I'm freer with my expression, though I still usually take into consideration the technical abilities of the typical professional musician, unless I am writing something like a concerto, in which case the solo part is written with virtuosi in mind and is considerably more difficult.1 point

-

So your later education spoiled your affinity as a composer for an historical style? That's tragic. I never finished my degree because I perceived that my professors were not going to let me be the composer I wanted to be, but I have always regretted not sticking it out. I usually advise young composers to go ahead and study composition, learn what they teach you as a body of knowledge, write what they tell you to write, but do your best to remain true to who you really are as a composer, whatever that may be. If the system brainwashes the student to the point that that's not possible, even in a few cases, perhaps I should reassess that advice. I'm sorry for your experience - from your tone, I can tell it has embittered you somewhat, and I can't say as I blame you.1 point