Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 04/22/2020 in all areas

-

1 point

-

Just a simple piano theme I've been experimenting with. Wanted to capture the theme of Passion with some Fury.1 point

-

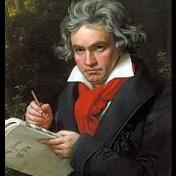

The way I see it, the texture (or textures) should be used in accordance with what you are trying to express in the piece. In the case of chords in music, you should choose what to use based on the emotion of the piece, or section within the piece. Beethoven's thick chord texture in the Pathetique Sonata introduction was chosen to create a dramatic and animated effect, whilst Chopin's lighter chord texture in his C minor nocturne was used to create a sadder, more melancholic effect. They well could have chosen any texture; for example, Beethoven could have used a texture similar to Chopin's, or Chopin Beethoven's. But instead, they chose the textures they used, because for them, it best conveyed what they were trying to express. Ultimately, I think it comes down to what you personally wants to say. Of course, somebody can suggest ideas to you, and you may like those ideas, but ultimately, it's what you believe works best for the piece. As for the rules set in the past, I would say feel free to use them, or break them; whatever best serves your musical message. (But personally, I would not recommend breaking rules just for the sake of breaking them, or following rules just for the sake of following them. Then you're only writing music for the theory's sake, not the music's sake.) In regards to not muddying chords, then I think it's probably best to change the pedal within a "chord-y" section frequently as possible; for example, every change of harmony. But again, if the desired effect is to have a muddy section, then by all means use it. Whatever you think is most beautiful for your piece.1 point

-

The easiest way to make you chords "clean" is by making the lowest voice the tonic or either the fifth. I would say that the "mudiest" of all inversions is the first inversión specially in major chords because of the minor 6th. Like all the others said, the piano has changed and today has more ressonance that before so, things that in 1800 sounded well, today can sound a little muddy. Idk if someone has already recommended but, try to listen to rachmaninoff, his music is the more clear modern example of thick chords without being muddy. Honestly is impressive to see 10 notes chords. I think his dark style fits perfectly with beethoven (talking about chords), because in music he is a LOT different.1 point

-

Sounds exquisite! If either of you guys @Guillem82 are interested in collaborating it would be fun to get a new perspective on things.1 point

-

Beautiful work. The development of the theme is very natural, and all underpinned by lovely harmonies. I'd never heard of Dzerzhinsky before this - perhaps one to check out! Thank you for sharing.1 point

-

This is Marvelous. You are very talented. I concur with many of the comments on the YouTube forum. Is this a recorded performance, or a MIDI rendition? If I am frank there is too much human emotion in the performance to pass off as a computer! 😄 You have perhaps converted me to your style of work from the tedious galant, cliche ridden patterns that I for whatever reason chose to specialize in haha! Thank you for sharing.1 point

-

Closed voice bass chords just don't work on the modern piano as well as they did on the fortepiano. There's far to much resonance. Also, most pianists would pedal large chords to get the most resonance possible from the instrument. You can have open voiced bass chords and still get the same resonance from the chord. Maybe a chord built:10th/5th/Root can still work. Debussy famously said that he refused to write pedal, because every piano is different and one pedalling will sound great on one piano and awful on another. It still applies today, with so many different pianos. Don't expect your performer to pedal only exactly where it is marked. Let's have a look at some examples from the piano literature. First up, Grieg! The passage starts at 1:03 There's a melody formed from chords, but it doesn't fulfill any of your three criteria. Now some Beethoven, seeing how you always talk about him. Sonata in C Major, Op 10 No. 3: The 4th movement start at 20:22. It's a melody from chords. It's not slow, dramatic or a chorale. There must be countless other examples that don't fit what you said. It's easy enough to write a melody with chords. On the modern piano, yes you are. You can just spread the notes out a bit more, without bringing the whole chord up an octave. In fact, that solution doesn't really help anything, it just makes it less noticeable. I'll leave you with one last example. Look at how Rachmaninoff voices his chords in the well-known Prelude in G minor.1 point

-

I have listened to Symphony no. 5 and Symphony no. 6 by Beethoven and I noticed that they are like Yin and Yang, polar opposites on the outside, but deeply connected on the inside. Symphony no. 5: "Fate Symphony" - Yin Symphony no. 5 is like the Yin in Yin and Yang, it is the darker of the two symphonies. It starts in C minor and a lot of the key areas, both tonicizations and modulations, can be traced back to C minor via close relations. D major? It is the dominant of the dominant. F minor? That's the subdominant. C major? That's the parallel major. The first movement alone has this feel to me of wanting to resolve to a major key, but every time it reaches a major key, it gets crushed by C minor yet again. Even the second movement, which is in a major key, still has this battle of dark vs light feeling to me, where Ab major is the darker of the 2 major keys and C major is the brighter of the 2 major keys. The Scherzo, like the first movement, is in C minor, but it is a more mysterious C minor than the powerful C minor of the first movement that crushed every instance of major keys in sight. Over the course of the Scherzo, C minor becomes less and less powerful until it barely even makes a ripple as it finally resolves to a major key like the first movement alone wanted to do. It is as though Beethoven said: Symphony no. 6: "Pastoral Symphony" - Yang This symphony is a far cry from the drama of the fifth symphony. Instead of minor being predominant, it is rare. More of the key areas in this symphony, minor ones included, are distantly related. For example, the Bb to D modulation in the development of the first movement is an example of chromatic mediants. D major is also distantly related to F major via the same relationship, chromatic mediants. E major, it too appears in this symphony and it is a chromatic mediant of C major, the dominant of F major. A major is also a chromatic mediant of C major and is a key area in this symphony. The only real drama that occurs in this symphony is the stormy fourth movement. And even then, it is very brief, lasting only about 4 minutes, the last minute of which is the transition back to major from the minor key of the fourth movement. Deep connections between the 2 symphonies Despite these 2 symphonies being polar opposites on the outside, there are multiple deep connections between these 2 symphonies. First off, these symphonies were composed around the same time as each other and around the same time as Beethoven's fourth piano concerto. These symphonies were also premiered on the same day as each other and the same day as the fourth piano concerto in a big concert that was 100% Beethoven works. But time is not the only connection here. There are other connections too. Another connection that these 2 symphonies have is that they are both primarily based on motives. The interval of a third is also a connection between these 2 symphonies. In the Fifth Symphony, this mainly presents itself as the Fate Motif, though a lot of the key areas of the symphony can also be related by thirds. In the Sixth Symphony, this interval of a third mainly presents itself as Chromatic mediant relationships between keys. The way the motives get developed in the Development sections of the first movement of these consecutive symphonies is also similar. In both symphonies, a motive gets developed for a while until it breaks down into 2 notes. In the Sixth Symphony, this development is mainly through repetition and imitation. In the Fifth Symphony, this development involves a lot more changing of direction, harmony, and orchestration. Also, in the Fifth Symphony, this breakdown proceeds further than it does in the Sixth Symphony. It goes from 2 notes to 1 note, almost spelling doom for the Fate Motif, before Beethoven brings back the energetic eighth notes and the rhythm of the original Fate Motif. Both symphonies also involve parallel key relations. In the case of the Sixth Symphony, this is between F major, the key of both the first and final movements and F minor, the key of the fourth movement and that is the only place where I really hear a parallel major/minor relationship. In the Fifth Symphony, this parallel key relation is between C minor and C major and it is present in all the movements as foreshadowing of the C major finale in the first, second, and third movements, and as a C minor Scherzo moment in the Finale.1 point