Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 08/04/2020 in all areas

-

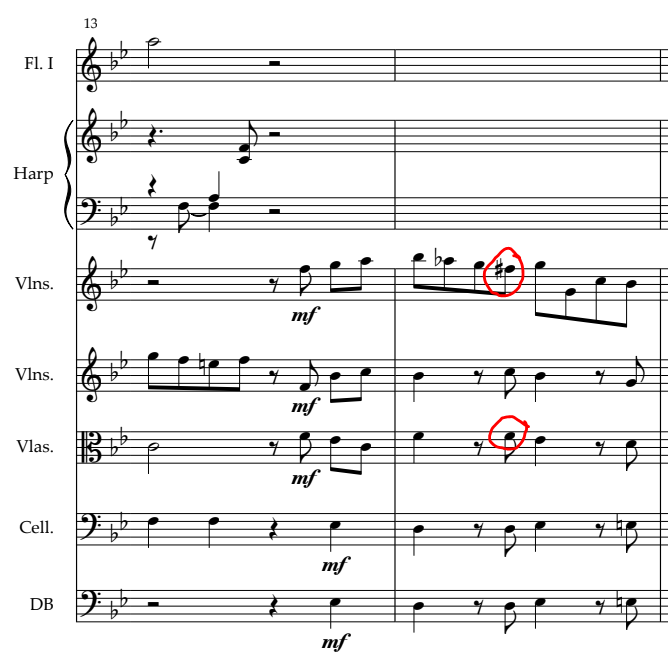

Absolutely right about F# and Fnatural simultaneusly. That was my mistake. Viola was out of the place and violin II was not the best option. A-G on violin II is also much better to give a complete harmony of DM7 and also avoid voice crossing when violin I makes the octave leap G-G. Thanks for the observation 🙂. About the orchestration first I wanted first I wrote it only for strings and harp, but I like I also like the mellow sound of the winds. Then I tryed doubling the 3 upper lines with 1 flute and 2 clarinet, because I find both fit very well with the harp, but there was too much doubling. Finally I kept just the flute without doublings. I didn't have any composition with that arrangement as a reference, but good idea about Scheherezade, I will have a look at the second movement. Korsakov is a great orchestrator and maybe I can take some ideas from there. Thanks for your comments and tips @gmm it was very helpful!1 point

-

Really nicely done! I really like the melodies you came up with, they are paced very well and reach their climaxes very effectively. The contrapuntal lines are all very interesting, and you use accidentals very well to add harmonic interest. I also like the way you orchestrated it and voiced the melody between the different iterations. One thing I noticed is in m. 14 you have the violins playing an F#, while the violas are playing an F natural an octave below, was this intentional? The minor 9th might be a little dissonant compared to the surroundings, maybe change the violas to an F# on the upbeat of beat 2? There are several spots were this melody returns and I think it's the same in all of them. (As an aside, I think it might sound cool if the cello and basses played an D# on the upbeat before the E on beat 3. Just a thought, feel free to ignore, I'm just biased because I'm a sucker for chromatic bass lines 😅) I always try to think of an example from a well known composer that is similar to what I'm trying to do. Off the top of my head, near the end of the second movement of Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherezade there is a section with flute solo, harp, and strings, you might check it out and see if it helps. It's quite a different texture than what you have here, but it might help. Was there a composition similar to this that you had in mind when you composed this? If so, I would start there. Out of curiosity how did you decide the instrumentation? If you're concerned about the flute getting lost you could possibly double with an oboe or clarinet, at least where appropriate. Lastly, if you're using Vienna Instruments I might consider fine tuning the performance a bit. I've never used VI before, but I understand they are pretty high quality, and I would think you could get a more convincing performance out of them than you have here. Your audio is certainly not bad, but with those kinds of tools it could be a lot better. I enjoyed listening, thanks for sharing!1 point

-

It's a very nice piece for a child. But the sooner he gets familiar with changing the pattern in the left hand, the better. Many people rely on a fixed accompaniment and the music becomes boring. No need to change all the time, but it's good to introduce new shapes along the piece. Not focus only on the melody.1 point

-

This post will be my opinions and takes on the string quartet, that will apply to all genres of the string quartet. For anyone who is interested in writing string quartets, I shall try to give my best unorthodox pointers and tips on how to make a string quartet better, and utilise each instrument to the best of its ability. Personally, I am an amateur string player since young who has both avidly listened to and played numerous string quartets and I tend to take inspiration from the quartets that I listen to while composing my own quartets. Now, let me discuss some of the pointers: 1. Make as much contrast as possible. Be it a major key, minor key, loud, soft, monophony or polyphony, I believe that contrast is the single most important essence to a good quartet. A good quartet needs a lot of contrast, to keep the quartet interesting to the ear and creates variety in sound. No one instrument should overpower the others in the melody and relegate the other instruments to a form of accompaniment for the entire piece. Playing some of the accompaniment parts personally before, it can be rather dull for them and it creates a dull effect where there's not much dialogue or antiphony between the instruments. One often overlooked way to create contrast is through the texture of the quartet. However, I disagree with the notion that counterpoint should be used at all times and to avoid parallel motion or chorale-like melodies at all costs. While counterpoint is very good at creating unique quartets and is key to a good quartet, when used correctly, parallel motion or monophonic themes across all instruments can elevate a quartet to another level (especially in a climax of a piece). It should be used sporadically at key moments during a piece, to highlight a certain motif or theme, or contrast an otherwise fully polyphonic section, one example of this brilliantly done is the opening of Beethoven's Grosse Fugue. There are many ways to create contrast, and after studying many quartets I realised that every composer has a unique way of creating that sense of contrast in their pieces. It's important to find one's preferred method to develop contrasts in their quartet. 2. Make more use of multiple stops. Double stops is a great way to add challenge and a unique texture to a quartet. However, it may be daunting for composers who have never dealt with strings. For this, I would advise that (90%) double stops with intervals 8ve or less in a chord are playable (the occasional 10th is possible but not for prolonged periods), and for triple/quadruple stops, try to stick to 5th or 6th intervals between individual notes to be safe. The exception to these rules is always the open string. As string players do not need to place their left hand fingers down when playing open strings, any interval that can use the open strings tend to be much easier for a string player to manage and allows for greater intervals between notes. 3. (Good) transitioning is much harder than meets the eye. For myself, I started composing more than a year ago. Still, even with my prior experience with string instruments and repertoire, it took me >20 tries across 7-8 different pieces to get transitions to a decent state. (I was working on string orchestra pieces back then, similar to the quartet) Even now, I wouldn't call myself a good composer in transitions and I still frequently struggle with transitions. The main difficulty of transitioning especially in a string quartet is not so much like orchestral or solo pieces, where you can find a pivot chord and modulate quickly without a hitch. Rather, it is because of the string quartet's unique nature where frequent contrasts in the music are required and the counterpoint across different instruments that makes it hard. Trying to bridge a very loud, climatic section with a very soft, intimate section within the span of a few bars is very daunting in string quartet writing. If anyone is interested, I can make an entirely separate post just on transitioning and some methods I have picked up through prior work on string writing. 4. Don't be afraid to cross registers. Some composers who are new to quartet writing often view the string quartet as SATB writing for strings. While this has some merit, this is not entirely true. String quartet writing is very fluid in the fact that there are many styles. In romantic and 20th century string quartets, it is very common for the registers of different instruments to continuously cross over one another to create variety and effect. Any instrument, even the cello at times, can take the highest register out of the 4 instruments at any given point of a quartet. (This is why many quartets let the cello play up to even D7 or two octaves above middle C frequently!) Don't hesitate to try crossing the registers of the different instruments over, and a good place to start would be with the viola and cello alternating registers. 5. Practice makes perfect. This is especially apparent for string quartet. No matter how much analysis of famous quartets, the best way to compose a good quartet is through prior practice. It took me many tries to at least reach a decent level in string writing. Try practicing across a wide range of styles and genres of the string quartet 6. Lastly, string quartet is not a dead medium. This was actually a view held by many late Romantic/Impressionistic composers, who felt that String Quartet was a dead medium where not much new styles or forms can be pioneered and all possible iterations and styles have been exhausted. This is why many of such composers (Debussy or Ravel) composed only one quartet. However, this was clearly proven otherwise when 20th century composers turned the medium on its head and pioneered an entirely new way to compose the string quartet. Some composers now have the same view as the Late Romantic composers. However, string quartet is one of the most flexible and versatile mediums of classical music to date. It differs so greatly, from the classical quartets of Mozart and Haydn, to the Romantic Quartets of Mendelssohn and Dvorak, to the 20th Century Quartets of Shostakovich and Gliere. There is still so much more to discover for the string quartet and there are many examples where one-of-a-kind quartets have been produced. Let me just name an example: Grieg's String Quartet No. 1 in G Minor was very eye-opening for me. It is a very unique string quartet that focuses on the resonance of the open strings of string instruments and the virtuosity of its players. It is very intricate and heavily utilises double stops throughout its piece, to the point where even the original publisher rejected it for having too many double stops. However, it was indeed playable and it gave rise to a new form of string quartet, with its lyrical, fast-moving melodies and its sonorous sound, yet filled many sharp contrasts. I would suggest to anyone who is bored of string quartets to listen to this, and possibly gain inspiration. Such a unique thinking of the quartet has not been thoroughly explored yet and I urge others to explore the resonance of open strings in string quartet as sort of a challenge to anyone composing future string quartets haha this is the link to the quartet: This post will be my opinions and takes on the string quartet, that will apply to all genres of the string quartet. For anyone who is interested in writing string quartets, I shall try to give my best unorthodox pointers and tips on how to make a string quartet better, and utilise each instrument to the best of its ability. Personally, I am an amateur string player since young who has both avidly listened to and played numerous string quartets and I tend to take inspiration from the quartets that I listen to while composing my own quartets. Now, let me discuss some of the pointers: 1. Make as much contrast as possible. Be it a major key, minor key, loud, soft, monophony or polyphony, I believe that contrast is the single most important essence to a good quartet. A good quartet needs a lot of contrast, to keep the quartet interesting to the ear and creates variety in sound. No one instrument should overpower the others in the melody and relegate the other instruments to a form of accompaniment for the entire piece. Playing some of the accompaniment parts personally before, it can be rather dull for them and it creates a dull effect where there's not much dialogue or antiphony between the instruments. One often overlooked way to create contrast is through the texture of the quartet. However, I disagree with the notion that counterpoint should be used at all times and to avoid parallel motion or chorale-like melodies at all costs. While counterpoint is very good at creating unique quartets and is key to a good quartet, when used correctly, parallel motion or monophonic themes across all instruments can elevate a quartet to another level (especially in a climax of a piece). It should be used sporadically at key moments during a piece, to highlight a certain motif or theme, or contrast an otherwise fully polyphonic section, one example of this brilliantly done is the opening of Beethoven's Grosse Fugue. There are many ways to create contrast, and after studying many quartets I realised that every composer has a unique way of creating that sense of contrast in their pieces. It's important to find one's preferred method to develop contrasts in their quartet. 2. Make more use of multiple stops. Double stops is a great way to add challenge and a unique texture to a quartet. However, it may be daunting for composers who have never dealt with strings. For this, I would advise that (90%) double stops with intervals 8ve or less in a chord are playable (the occasional 10th is possible but not for prolonged periods), and for triple/quadruple stops, try to stick to 5th or 6th intervals between individual notes to be safe. The exception to these rules is always the open string. As string players do not need to place their left hand fingers down when playing open strings, any interval that can use the open strings tend to be much easier for a string player to manage and allows for greater intervals between notes. 3. (Good) transitioning is much harder than meets the eye. For myself, I started composing more than a year ago. Still, even with my prior experience with string instruments and repertoire, it took me >20 tries across 7-8 different pieces to get transitions to a decent state. (I was working on string orchestra pieces back then, similar to the quartet) Even now, I wouldn't call myself a good composer in transitions and I still frequently struggle with transitions. The main difficulty of transitioning especially in a string quartet is not so much like orchestral or solo pieces, where you can find a pivot chord and modulate quickly without a hitch. Rather, it is because of the string quartet's unique nature where frequent contrasts in the music are required and the counterpoint across different instruments that makes it hard. Trying to bridge a very loud, climatic section with a very soft, intimate section within the span of a few bars is very daunting in string quartet writing. If anyone is interested, I can make an entirely separate post just on transitioning and some methods I have picked up through prior work on string writing. 4. Don't be afraid to cross registers. Some composers who are new to quartet writing often view the string quartet as SATB writing for strings. While this has some merit, this is not entirely true. String quartet writing is very fluid in the fact that there are many styles. In romantic and 20th century string quartets, it is very common for the registers of different instruments to continuously cross over one another to create variety and effect. Any instrument, even the cello at times, can take the highest register out of the 4 instruments at any given point of a quartet. (This is why many quartets let the cello play up to even D7 or two octaves above middle C frequently!) Don't hesitate to try crossing the registers of the different instruments over, and a good place to start would be with the viola and cello alternating registers. 5. Practice makes perfect. This is especially apparent for string quartet. No matter how much analysis of famous quartets, the best way to compose a good quartet is through prior practice. It took me many tries to at least reach a decent level in string writing. Try practicing across a wide range of styles and genres of the string quartet 6. Lastly, string quartet is not a dead medium. This was actually a view held by many late Romantic/Impressionistic composers, who felt that String Quartet was a dead medium where not much new styles or forms can be pioneered and all possible iterations and styles have been exhausted. This is why many of such composers (Debussy or Ravel) composed only one quartet. However, this was clearly proven otherwise when 20th century composers turned the medium on its head and pioneered an entirely new way to compose the string quartet. Some composers now have the same view as the Late Romantic composers. However, string quartet is one of the most flexible and versatile mediums of classical music to date. It differs so greatly, from the classical quartets of Mozart and Haydn, to the Romantic Quartets of Mendelssohn and Dvorak, to the 20th Century Quartets of Shostakovich and Gliere. There is still so much more to discover for the string quartet and there are many examples where one-of-a-kind quartets have been produced. Let me just name an example: Grieg's String Quartet No. 1 in G Minor was very eye-opening for me. It is a very unique string quartet that focuses on the resonance of the open strings of string instruments and the virtuosity of its players. It is very intricate and heavily utilises double stops throughout its piece, to the point where even the original publisher rejected it for having too many double stops. However, it was indeed playable and it gave rise to a new form of string quartet, with its lyrical, fast-moving melodies and its sonorous sound, yet filled many sharp contrasts. I would suggest to anyone who is bored of string quartets to listen to this, and possibly gain inspiration. Such a unique thinking of the quartet has not been thoroughly explored yet and I urge others to explore the resonance of open strings in string quartet as sort of a challenge to anyone composing future string quartets haha (link to Grieg's string quartet: https://youtu.be/OM9hdCpdcqc ) That concludes my rather lengthy post on the string quartet, let me know if anyone wants me to delve into other parts of the string quartet. Happy composing! Edit: I should have posted this on another forum, I didn't realise this was for incomplete works and writers block, sorry1 point

-

"and I honestly feel it is under-appreciated by modern composers as it tends to fall under the stereotype as vanilla and uninteresting." Agree entirely and it seems to come into its own when a composer has something more personal to say - perhaps I'm wrong but whereas an orchestra is a machine, a small ensemble is a collaboration of individuals each interpreting their lines within a cohesive whole. They 'speak' individually but the whole is greater than the sum of their individual messages. It's something that new composers should go for. The possibility of performance is greater than an orchestral work; even a beginner amateur quartet can play simpler compositions. And it's still my belief that if you can write effectively for a string quartet, explore its many possibilities, then you can write for a string orchestra - and if you can do that effectively then you can write for orchestra. I feel that those who regard a string quartet as vanilla haven't even started to open up their aural imagination - and all their compositions will be vanilla....until they wake up. Of course there are variations - a string quintet (with double bass or some other combination) a sextet, etc. But the basic quartet is to me unlimited. Interesting discussion, this. The only thing I'd add to your opening post is - don't be afraid to be bold. (Obviously, don't be impossible but within what's possible, don't be afraid to do it. Question is - what's possible?) For a new composer who isn't a string player it means listening, score study perhaps and reading-up to be sure they know what the different articulations are about. Then use them appropriately. (Edit: Oh, ok, re-reading your post it looks as if you did more or less say that after all.) .1 point

-

@Quinn Yea that's exactly what I mean haha transitioning encompasses a large range of topics but essentially it just means changing from a certain type of timbre/instrumentation/mood/key etc. to another within the same piece. Basically any type of bridging musical material between two major sections of a piece that may have different textures, dynamics, keys etc. I use transitioning as an all-encompassing word to mean that for quartets, it is important to make the music sound well-connected and make it "flow" by having good transitions between subjects rather than a hodge-podge of musical ideas that don't fit together or have weak transitions. Yea I have to admit that being a string player is a really big advantage when it comes to quartet writing. Being able to understand the intervals that are playable for multiple stops is a huge plus, along with the obvious that you can visualise how each part will sound like in a live playtest. The great thing about string quartets is the nuanced changes in textural quality like muted and open strings as you mentioned, as well pizzicato and even modern techniques such as snap pizz. and sul ponticello which add a whole new dimension to the modern string quartet. It is a fast-evolving style and I honestly feel it is under-appreciated by modern composers as it tends to fall under the stereotype as vanilla and uninteresting.1 point

-

Yes: transitions are needed, sometimes forgotten, of justified with "it's a contrast". Contrast and transitions are not enemies.1 point

-

Nice intro and melody, although it often relies in black notes. I would remove the drums, which are at a fixed pattern. A bass would fit better.1 point

-

1 point

-

Its a catchy melody and a middle attractive section. I would try to explore changing in some repetitions or parts the left hand pattern.1 point

-

Thanks for the feedback, James. I was concerned Id gone too far with the reverb but I did want to place the sounds in a vast space, so I'm glad this comes off. I did add a drive plugin to the cymbals as they didn't have enough bite - I will lookout for excess distortion in future pieces. Cheers!1 point

-

One thing that I don't think has been mentioned that you might find helpful... learn some music history. Pick up biographies of a few well-known composers from the library, read the biographical information on their wikipedia page, or go watch some youtubes about them and their careers. Times have changed a lot since Mozart, Beethoven, and Bach, but some things have not. Bach was a church organist. Vivaldi was a music teacher for a girl's school. Mozart's "Requiem" was commissioned by an amateur composer who liked to pay better composers to write works which he then pretended to have written himself. Looking at how the big name composers careers developed can help you get a sense of what is actually a good career path, when it is worth doing some unpaid work, how much time to spend on your composing education vs. taking piano lessons, what kind of other jobs successful composers tend to have, etc. The idea here is not to learn every little fact about a composer's sonata, but what their education and career looked like. What would their resume look like if you could see it, condensed down to one page? Did family help them pay the bills or introduce them to an internship while they got started? Did people like their music right away? Did they get into every music school they applied to? Did they get every job they applied for? Were they ever full-time composers? How did they get their scores into the hands of people who passed them down, and passed them down, so that we still know their music today?1 point