You know, I like this piece a lot. You break out of your usual style of writing here, creating a balanced contrapuntal texture that is not dense, with plenty of nice sequences and imitation that brings contrast (the hockets like in mm. 19 to 21 are great). I also don't agree with some of the things @Guillem82 mentioned: I don't see or hear any harmonic mistakes/unresolved dissonances, and I don't mind the doubled notes on the violin. Sure, it's uncharacteristic but in this case it works fine, just like the distant modulations.

Moving on to things I don't like...I would surmise it as:

There is no apparent organisation or plan of your musical motifs.

Let me elaborate. Regarding the first point, I remember saying to you before to analyse what Bach does in the WTC with his fugue subjects in order to get an idea of how to develop them (the formal term is fortspinnung). I really would like to make this recommendation again. It is not just fugues, or even Baroque music that this skill applies to - a control and constant development of a limited number of musical ideas is a trait of virtually all classical music. Especially in contrapuntal music, a failure to do this ends up making much of your music "noodling", where you have correctly constructed melodies, harmonies and parts that work with each other, but virtually zero connection between one bar and another.

As an example, when I wrote the fugal section of the Overture of my Keyboard Suite, I recognised that the driving rhythm will be 6 semiquavers-per-bar. To achieve motivic unity, I limited myself to three possible settings of notes to this rhythm: an ascending scale, a turn figure (both of these can be found in the subject), and a rising fourth from the 2nd to 3rd notes followed by a descending scale (found in the countersubjects). You can check for yourself that except at structural cadences, every group of 6 semiquavers in the 242-bar long piece belongs to one of these three settings or their inversions. This is a somewhat extreme example; the Air for example is far more loosely bound by motifs, but I stand by my point.

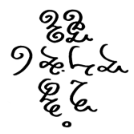

When you look back on your fugue, ask yourself: what is it that ties the whole work together? To me, it's certainly not the subject! The lack of subject entrances aside, the head (very nicely composed) has a characteristic descending, dotted, pattern

which completely disappears after the first few bars! The tail (also very nicely composed) comprise of a descending scale and a rising seventh chord in quavers. Both of these elements return very rarely for the rest of the piece.

So, if your core musical idea isn't actually the subject, what is it?