-

Posts

206 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

7

Fugax Contrapunctus last won the day on April 9 2025

Fugax Contrapunctus had the most liked content!

About Fugax Contrapunctus

- Birthday July 15

Contact Methods

-

Website URL

https://www.youtube.com/@fugaxcontrapunctus?sub_confirmation=1

Profile Information

-

Gender

Male

-

Occupation

Student

-

Interests

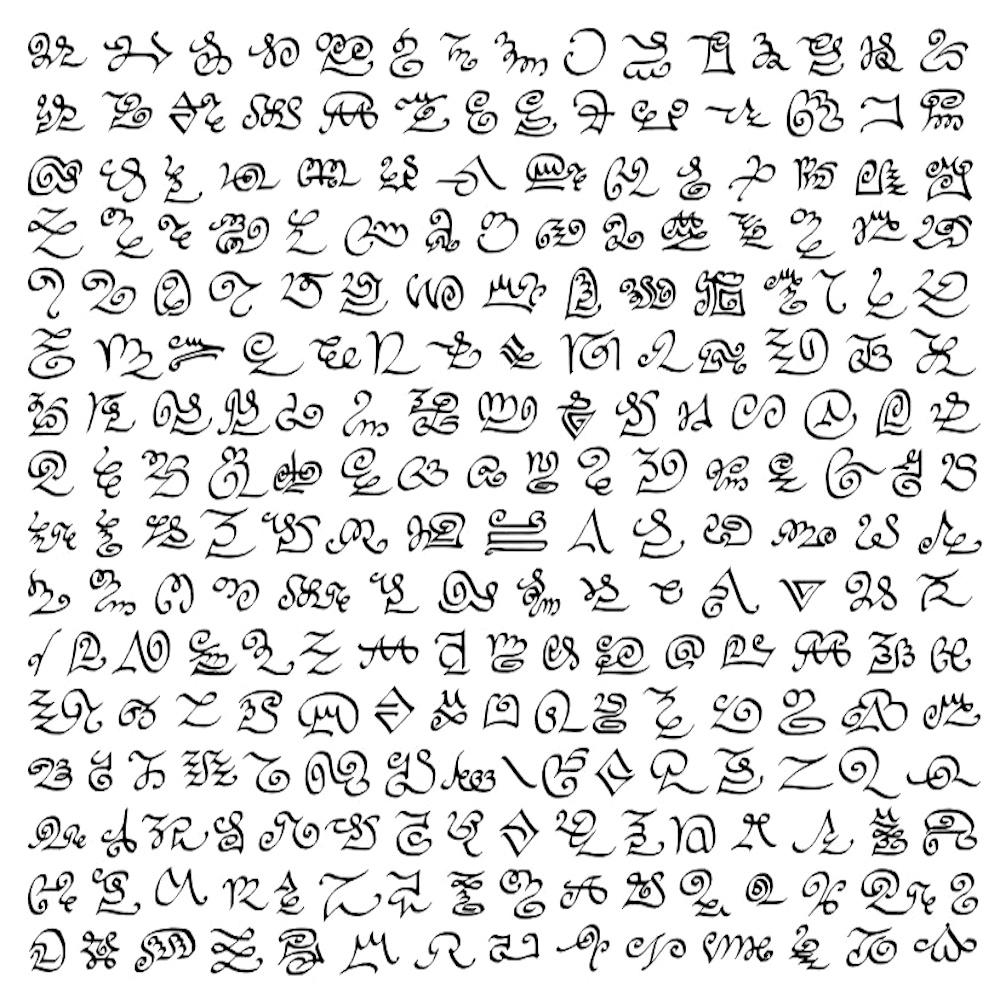

Composition, language learning, philosophy, conlanging and worldbuilding

-

Favorite Composers

J. S. Bach, Scarlatti, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Brahms, Chopin, Tchaikovsky, Liszt, Mahler, Rachmaninov, Prokofiev, etc.

-

My Compositional Styles

Contrapuntal neo-Baroque

-

Notation Software/Sequencers

MuseScore 3 & 4

-

Instruments Played

Violin, piano

Recent Profile Visitors

6,421 profile views

Fugax Contrapunctus's Achievements

-

Greetings @Wieland Handke! The response I was writing got lost when I tried to post it, which saddens me considering I went on a very long tirade about how Bach's music cannot conceivably be surpassed and how my admiration for his genius renders my own works insignificant in my view, but perhaps precisely for that same reason it's for the better that such a reply will never see the light of day. At times even I grow concerned by my absolute devotion towards Bach, so stating the obvious a thousand times with different words would only further make it seem like an unhealthy obsession. As for the canons in Die Kunst der Fuge, there are actually 4: Contrapunctus XII at the Octave - in Hypodiapason/alla Ottava, XIII at the Twelfth - alla Duodecima in contrapunto alla Quinta, XIV at the Tenth - alla Decima in contrapunto alla Terza (not to be confused with Contrapunctus XIX, the unfinished Fuga a 3 Soggetti, which is usually presented as Contrapunctus XIV in most of the modern versions that omit the canons) and XV in Augmentation and Inversion - per Augmentationem in Contrario Motu/al roverscio et per augmentationem. There is also one more, found in the Appendix of the Art of the Fugue and often relegated to obscurity in most editions for that very reason, as well as probably because the beginning of its theme until the entry of the 2nd voice is identical to that of Contrapunctus XV, and only then diverges: the canon in Hypodiatessaron al roverscio et per augmentationem perpetuus. As you can see, the format of the title itself had a far greater impact on my own canon's technical conceptualization than the music itself. And regarding the point you're making, I am rather inclined to agree. Shunske Sato arranged the Netherlands Bach Society's recording of the Art of the Fugue so that every couple movements, a chorale would be sung. Perhaps my own canons could serve as interludes instead of being the focal point of a given programme or concert cycle, though for such an outcome a far more monumental and extensive work would need to be composed first.

-

Since this is in essence a revised version of my earlier Enharmonic Perpetual Canon No. 3, whose single contrapuntal flaw replicated across all voices required a modification of an octave leap which ultimately ended up necessitating a transposition of the whole canon a perfect fourth higher, I decided to change the title of the entire series thus far to "Pantonal Perpetual Canons", as the previous title didn't quite serve as an accurate descriptor of the technicalities within the compositional process that gave rise to these pieces. Due to the necessary integral transposition of this work, however, the coda's newly resulting ending key (F-sharp/G-flat major), the only key along with its relative D-sharp/E-flat minor that displays an equal number of accidentals when enharmonized, far too many inconsistencies relating to the enharmonization of melodic intervals can be found in this version. Normally I would have managed to transcribe the melodic theme across all its internal transpositions in a way capable of satisfying apparent melodic continuity throughout the notation process, but due to the ambivalent quality of this key when it comes to enharmonization, not even the coda could be perfectly transcribed without far too many double accidentals. As such, as much as it irks me to see it like this, I have had no choice but to leave the currently notated version of this canon as is. The choral lyrics of this canon (once again, in Latin) translate as follows: "Change is inevitable in all things. Everything flows in the balance of those who are tempestive." As for the coda, its own lyrics further drive the meaning of these aphorisms to greater clarity and realization. YouTube video link:

-

Greetings @Wieland Handke! The F-natural in bars 3 and 4 of the 1st and 2nd entry is very much intentional, even though it does generate a certain degree of instability not present in the original, fully tonal rendition of Mozart's own canon. In fact, I should thank you for highlighting the matter of accidentals, as the previous version did not, in fact, feature completely real transpositions of the theme. There were a handful of mistakes every 3rd bar, not contrapuntal, but harmonic and thematic, as the continuity and integrity of the transpositions was broken with leading tone and its minor 3rd/5th of a dominant chord being raised a semitone higher. All of that has now been corrected, so unless any more oversights of mine were to resurface, every single entry should now be a real transposition to the lower major 2nd of the main 18-bar-long subject. I'm glad to learn that the current length of this canon would prevent it from seeming far too repetitive to the eyes of an educated listener. Indeed, I was worried it might end up sounding excessively mechanical despite the flowing timbre of legato strings, as monotony may distort even the most sophisticated of musical devices into pure pure noise after far too many identical, tiresome reiterations. It's a relief to know that to you it did not appear to be the case here, and I must thank you for your acute observations, for otherwise I might not have come to realize that the transpositions were not 100% exact. I should also probably check @PeterthePapercomPoser's take on the Persichetti exercises, especially considering this canon on different scales you just mentioned. I'm anticipating a gold mine of modal/post-tonal contrapuntal solutions! Thank you for this recommendation as well.

-

So I decided to convert the theme of Mozart's perpetual canon at the 2nd for String Quartet in C major (KV 562c) into one of my enharmonic canons by keeping the same melodic intervals across all its entries. As opposed to the four previous installments of this genre, this one is exclusively instrumental, as I struggled to redistribute the voices so that the theme would fit the vocal ranges of a 6-part choir. Partly for the same reason, the string sextet section is comprised of 4 violins and 2 cellos, as the viola ranges appeared unsuitable for the middle voices without significantly altering the whole structure of the canon. Neither is it technically a dual canon by tritone transposition as the others, but instead returns to its initial starting point without the need for a secondary repetition a minor 2nd lower per each iteration. This is due to the fact that, instead of following the circle of fourths, each entry starts a major 2nd lower from the previous one, thus having the first note of each of the 6 entries in this canon trace the whole-tone hexatonic scale back to its inception. YouTube video link:

-

The subject of this one first came to mind roughly 7 hours ago already in its current form, and realizing its potential I wasted no time in writing it down, lest I forgot its exact melodic contour whose progression has been able to accommodate for elaborate chromaticisms in the other voices. Now, after yet another sleepless night put to good use with tireless contrapuntal machinations, this little fugue for string trio is at last complete in my eyes. YouTube video link:

-

Fugax Contrapunctus changed their profile photo

-

Motet a 8 "O Magnum Mysterium" in E-flat major.

Fugax Contrapunctus replied to Fugax Contrapunctus's topic in Choral, Vocal

Indeed. The similarity in timbre of instruments within their respective families often tends to muddle the trajectory of individual lines amidst the density of the texture, as has frequently happened in my keyboard compositions even for just 4 voices. But the human voice still retains that distinct timbral quality to it, somehow capable of preventing its integration into a larger choral whole from forsaking the uniqueness of its sound and the meandering of its melody. A testament, perhaps, to how vocal music was upheld as the most sacred during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance; not just because of the references to the purported sanctity of the natural human voice in the Old Bible and the Gospels, but because its endless versatility and potential in conjoining doesn't undermine the independence of each line nearly as much as it otherwise does for mere instruments. Thomas Tallis himself certainly took this to the absolute non plus ultra with his renowned Spem in alium, and yet, the fact that 40 voices singing simultaneously may still be perceived as individually separate with each listening instance still leaves room for even more ambitious polyphonic endeavours to be produced (although it would certainly be beyond overkill to even try). Thank you kindly as well! Though unfortunately I have bad news concerning the languages supported by the current version of Cantāmus: In any case, I'm sure a real choir would be far more adept at singing in Polish than the vaguely synth-sounding lyric renderings Cantāmus usually provides, though of course such an eventuality would come at a far greater cost. Perhaps an online choir with individual part recordings being carefully timed and assembled together might do the trick. Otherwise, a live premiere with a professional choir would be my best bet. Either that or browsing the Internet for competitors, of which I know none whose lyric rendering quality comes even close to that of Cantāmus. -

Motet a 8 "O Magnum Mysterium" in E-flat major.

Fugax Contrapunctus replied to Fugax Contrapunctus's topic in Choral, Vocal

Greetings Henry! Under normal circumstances, such egregiously positive feedback would have me including several rephrases of "thank you" in my response. In your particular case though, I feel it is only proper that I answer with a wholeheartedly humble 不敢當, and for good reason. Of those among your 6-part compositions I've had the awe-inducing pleasure of listening to, your mastery of complex textures across vast swathes of music is on a completely different level, perhaps even unrivaled, dare I say. To mention the most prominent example, your String Sextet in G-flat major, does not merely fit the conventional definition of "masterpiece", but rather expands upon it beyond what was conceptually possible in my mind up until that point. Its technical perfection and measured balance of musical aspects excelled over everything I knew when it comes to structural integrity, modulatory prowess, stylistic variety, motivic resourcefulness, contrapuntal-device handling, internal narrative coherence, ...the list just goes on! Given I already wrote back then what was perhaps my lengthiest review ever on this forum, I won't repeat myself too much on the myriad wonders your work ellicited on me and continues to evoke every time I've listened to it since, but one thing I shall mention again: with 8 voices or not, my tiny little compositions are not even worthy of being mentioned remotely on par with such jaw-droppingly all-encompassing artistry in music you have developed and refined to such a great diversity of effects. What I am trying to say is: it means a lot to me to hear that you, whom I consider to be one of the greatest masters in our generation, are pleased with such a comparatively minor piece of mine, if there's even to be any comparison at all between this and your utmost proficiency in counterpoint both innovative and sublime. It may have two more voices than your 6-part compositions, but does it even matter when the brilliance of any of those far exceeds my whole production like a supernova outshining an entire galaxy? In the end, I can't help but appreciate the sheer generosity of your remarks, even if I ultimately feel undeserving of them in the face of the insurmountable magnitude and unparalleled quality of your output, but it is precisely because of such achievements that your words mean so much more to me, almost like the very enbodiment of the kind of composer I aspire to be guiding me along the right path forward. Thank you kindly, Henry. It truly is both an honour and a priceless gift to have thus met your approval. -

Greetings and apologies for my late response. The entire piece has been transposed one whole step upward in order to accommodate for the English Horn's playable range without altering its melodic line, as any other change to the main motif would undermine the periodicity expected of strict canonic imitation. Thank you for your patience in pointing out my mistakes. I hope this last modification has not negatively affected other instrumental or vocal ranges too much, though as far as I can tell every part is feasible now. Otherwise I'll have to apologize to The Sopranos as well. 😅

-

2025 Christmas Music Event!

Fugax Contrapunctus replied to PeterthePapercomPoser's topic in Monthly Competitions

Here's my submission! Perhaps I should have waited till Christmas Eve for its publication, though in the end I reckoned the sooner might as well be the better. P.S.: I wholeheartedly agree with the distressing concerns brought forth by @AngelCityOutlaw regarding the AI-generated music submitted for this event. It should go without saying that allowing AI-generated material to be presented on par with compositions requering hours upon hours of effort and dedication could run the risk of severly undermining the legitimacy and ultimate purpose of these community events, not just on account of the frictions and controversies caused by the presence and promotion of AI-generated content, but also on a more fundamental level which has been thoroughly implied over the course of this discussion. Despite this, I firmly believe those who want to participate and submit their art should not hesitate to do so. Why let so much time, effort and dedication go to waste after creating a work of art that is in any capacity worth far more than mere AI imitations? My take is that we should not be deterred, but rather emboldened in the face of these dire circumstances we are living through, that we may adapt to this unsettling trend and make our art known regardless. In fact, that's precisely why I think it's more important than ever not to refrain from posting our own music, lest we inadvertently pave the way for more of this AI-generated music to claim our place. It is rumoured that the Dead Internet Theory may as well soon become an increasingly encroaching and inexorable reality. By refusing to yield to the tide and sharing more of our own creations, hopefully we might briefly forestall such a harrowing prospect for this tiny little corner of the Internet where so many creative wonders are being posted and discussed every single day. The point is not to force these AI-generated compositions out by decree, but to make it so that the abundant music produced by humans in this forum may flourish beyond the scope of neural networks being used as amoral tools or shortcuts to achieve similar results in appearance, yet severely lacking in personal significance, emotional depth or even a core message capable of steering the course of the compositional process. Banning AI-generated music will not ameliorate the problem at large, but composing music through righteous hardship might as well be the only substantial antidote against the proliferation and normalization of this kind of content. That being said, I'm certain this must be quite a difficult point of contention for the forum's staff to deal with and try to find a meaningful solution for, so I won't comment further on the subject matter. In any case, I hope whichever resolution or agreement is reached on this issue will allow the course of these community events to carry on peacefully and with respect towards the time, effort and dedication proportionally invested into each submission. It is good to know that this matter is being seriously discussed by staff and high-ranking members alike, and as such I would like to thank @Henry Ng Tsz Kiu and @PeterthePapercomPoser among others for their dutiful labour in calmly trying to sort out things amidst the heat of the debate. -

In anticipation for this year's Christmas Eve, I decided to try my hand at writing another religious motet. Considering the fact that the bulk of this piece has been composed merely in the span of yet another insomnia-driven bout of inspiration, perhaps its modest length may as well be a reflection of missed potential, as I reckon it could have been developed into a more complex structure should its latter half not have got stuck on a protracted pre-cadential spiral. Once again, just as with my previous vocal fugue, the main goal of this composition was to make the text as intelligible as possible (specially taking into account the musical history of such a well-known textual setting), that is, within the confines and constraints of an 8-voice motet. This has ultimately led to some interesting contrapuntal oddities which, despite the preservation of independent voice-leading and thorough avoidance of melodic and harmonic blunders, have produced a number of somewhat unorthodox unresolved dissonances throughout. Nevertheless, I believe such contrapuntal licenses are more than sufficiently justified given the scope of this piece, as well as the sheer volume and density of its texture all the way through. This piece was specifically conceived as a submission for this year's edition of the forum's Christmas Music Event, and shall be presented accordingly in its dedicated thread. YouTube video link:

-

Greetings Henry. Indeed I had expected the similarities between the primary subject of BWV 1080 and the ones used here would end up seeming far too glaring. Perhaps it may serve as a testament to the versatile simplicity of this kind of subjects, whence far greater complexity may be properly built upon. In any case, another fair reminder of Bach's genius and the omnipresent influence of his fugal developments. With that out of the way, I must apologize for not replying sooner with regards to the recent calamity. I wholeheartedly hope none of your acquaintances were directly affected by the fire. I initially hesitated to properly dedicate it to the victims due to its magnitude and devastation, and especially because of the gruesome suffering, mourning, affliction and grief so many families and friends of the deceased must be going through, for which this humble composition of mine could never properly stand up to provide nearly enough consolation. However, I should have realized sooner that not acknowledging it at all would be far more insensitive and disrespectful towards the victims and their loved ones. As such, albeit rather late, the dedication has been included in the score document. My utmost condolences. 節哀順變。

-

And I thought those low D-sharps on the basses were far too excessive! I couldn't even bring myself to sing below a very awkward-sounding E despite technically being a baritone. I wonder how potent of a voice a deep bass singer must have for such a B-flat to be remotely audible as pitch instead of pure vibration. To me, such extended ranges seem far more extreme than the usual alto-contralto range, which I believed is usually cited to reach down to an F below the staff. In any case, the concern is understandable. This fugue was originally set for D minor, as much of a nod to Mozart's heavy association of death with this particular key as a matter of convenience in order to adhere to the standard ranges for vocal music, which as we know often tend to require more conservative estimates in choral settings. Unfortunately the digital choir soundbanks I'm using struggled far more just a semitone above in certain passages, with certain octave leaps in the tenor part sounding especially screechy, so in the end I was forced to choose the lesser flaw and thus had to resort to lowering the whole piece to its current key. I hesitate to even call it a double fugue, as what might appear as the 2nd subject is in fact merely derived from the first, and I certainly would not dare label it a triple fugue, despite the relatively minor changes undergone by the subject that would normally not be explained by a conventional tonal answer. The stretto treatment is undergone first by what could be considered the 2nd subject following its own development section, and only then does the stretto for the original subject come about, thus helping cement an overarching ABA' superstructure that unifies the piece as a whole beyond mere exposition, development, stretti and codae in cycling motion. As for the Christmas Music Event, perhaps I might be able to submit a proper piece before the deadline. As of lately I've been considering a 5-part motet rendering of "O Magnum Mysterium", though I may consider other related texts to the same effect. In any case, I'll let you know in the dedicated thread if I manage to finish anything suitable in time. Thank you for your review!

-

After undergoing plenty of struggle to find a proper textual setting capable of matching the rhythmic patterns of this vocal fugue, I decided to settle for an altered version of the "Libera me" movement commonly found on Requiem masses. Despite the minor changes required for the text to fit the subject of the fugue, its treatment throughout has been a conscious attempt to make it as audibly intelligible as possible, as opposed to the vast majority of my previous vocal works, where any regard for the text was completely secondary to the music. This composition, as well as its harrowing message, has been dedicated in memoriam to the victims of the Wang Fuk Court fire, which tragically befell Hong Kong on November 26th. May their souls find peace and eternal rest. 請安息吧! YouTube video link:

-

Wieland Handke started following Fugax Contrapunctus

-

Among all the other previously published canons of its type, this one might as well have turned out to be the most demanding to perform, in no small part due to the choir's conventional maximum ranges being reached in at least three voices, including both soprano (C6) and bass (E2), making it no small feat to sing. The main lyrics would roughly translate from Latin to English as follows: "In the direst of circumstances the true heart of men shall sing with great hope of leaving behind a memorable life. Even death can conquer those whose memory lies in the glory of their good deeds." The coda, as per usual, reinforces the core message in a variety of ways. YouTube video link:

-

As the third installment in my enharmonic perpetual canon cycle, this one follows a procedure nearly identical to that of the first one and is quite similar in duration as well. The lyrics (once again, in Latin) sung by the choir translate as follows: "Change is inevitable in all things. Everything flows in the balance of those who are tempestive." As with the previous installment, the coda further drives the meaning to greater clarity and realization. YouTube video link:

.thumb.png.8b5b433a341551e913a34392660bc95b.png)

.thumb.png.1e2763f479362bbb522da50d31ef2e50.png)