nojtje

Old Members-

Posts

74 -

Joined

-

Last visited

About nojtje

- Birthday 02/21/1988

Contact Methods

-

ICQ

0

-

Website URL

http://

Profile Information

-

Location

The Netherlands

nojtje's Achievements

-

you're right, they are harder on the fingers, but we're not that moany. as long as the piece isn't only black-key-glissandos, we're all right :)

-

So, how has it come off?

-

Okay, if anyone is still interested, I think this thread is a good one and I open the floor to subjects!

-

Oh and btw, wind players in general are fond of different articulations. Your motif is especially powerful because it combines legato with staccato, which is promising :huh:

-

I assume the piece doesn't have to be very long, seeing as you're down to having to do it in what, 3 days? Your motif is powerful in that it is easily recognisable provided it is set in a good register and in the right context. In other words, if you write some decent counterpoint, the piece should write itself. Remember that a quartet is basically chamber music, all the players are equally important and you as a composer have a duty to make them feel important. In other words, they will all have to state the motif at least once ;-). So what can you do with a motif that short? Beethoven wrote a whole movement based on a motif consisting of just four notes too. It's possible. Of course, he had an entire orchestra, so much more possibilities for contrast. You have to find contrast in other aspects, like I said, in contrasting counterpoint, different harmonic settings of the same material, rhythmic alterations... Seeing as you're writing for trombones, use their large range and have a look at a position chart to see which successions of notes it's easy to play quickly in succession. Sorry if I ramble a bit, but this is just what comes to me off the top of my head. Your motif seems to ask for a sort of loose, almost improvisatory treatment. You could explore it by really breaking it down to the 'atoms' of the motif, (for example the first two notes form an atom in my eyes, as to the third and fourth notes together, and the third up to the fifth is a 'molecule'), letting the instruments play around with these, 'finding' the motif as they go along, and then bounce the motif across all four players several times, experiment with different harmonies, transpositions and registers, and that will give you minutes of material :huh:. Good luck, and keep us posted.

-

Although I know what you mean, I think you should add a touch of nuance to that statement; it's a perfectly good thing to wonder 'what form defines a sonata' or whatever (to enhance one's understanding of the works by composers of another age), but I think you meant that nowadays it is not as useful to know 'how to write a sonata' or 'how to write a concerto' in the strict sense as it was in the past, when creating new music. At the bottom line, I think you're right though in saying that a concerto or even a sonata has no predefined form nowadays, because a concerto is nothing more than a piece to showcase one or more instruments and a sonata is just an elaborate way of taking material and working on it.

-

I volunteer to collect them. But maybe someone else is better fit, seeing that I won't be behind a pc from August 10th until the beginning of September. In response to Mark, I also said earlier that I hoped that other forum members would also take the time and trouble to comment on the subjects and say, from experience, why some things work better than others, before we have a host of subjects of which some make good fugues and others seem to trap you after a while. The learning experience is in knowing why some subjects trap you ;-).

-

Actually that sounds a bit weird.

-

Interesting you should say that, it hadn't occurred to me, but yes, the answer could actually utilise a neapolitan sixth. I did it differently though in my fugato.

-

Yeah, I figured in the meantime. Too bad really. If he's not coming back, maybe it's an idea to collect our own set of fugue themes and comment on each other and edit them so we have a set (maybe not even as much as 12) of solid, workable fugue subjects that we can start playing with? I've posted mine and am still eager to hear whether anyone has any comments regarding how workable they think it is and what would make it better in their eyes and in the light of their experience. BTW Mark, I will review your Pie Jesu today, I haven't got round to it, and there wasn't a hurry since you were away :)

-

I'd say, i) figure out which pieces have orchestra hits that you like ii) get hold of the score iii) see how it's done iv) compare different voicings and the different effects they create v) use this knowledge to your advantage and adapt it to suit your own ideas

-

What you should always try to do is listen to your piece from the point of view of someone hearing it for the first time. While you sleep, eat, and breathe your themes and motifs, someone hearing them for the first time will need to have them reinforced in several ways before a development even makes sense. And from my own experience I've found that when I felt that repeating something more made it boring, most listeners actually were glad that I took the time to relish that moment of music and spin it out. On the other hand, bearing in mind something Stravinsky said, paraphrased "many pieces of music end too late after they finish", you must be sure that the material you are using is actually worth a one-hour working. Some material requires a short, aphoristic piece: there is certainly a reason why Webern's music is often very short and concentrated. Again, it also depends on your personal style and flavour. While I don't like minimal music, which becomes boring very soon in my ears, I certainly appreciate the way an idea is gradually transformed in a way that you can hear every minute change. The question you ask is one that I have been struggling with ever since I began composing. What has helped me is to make a conceptual sketch of how I want the structure of the piece to flow, and what kind of things you want to achieve in the development. While you refer to it as a stream-of-consciousness, you really have to be careful that you write only notes which have a meaning so as not to alienate your listener. That is, if you want to take your listener on a 'journey'. If you wish to, well, drop him in a field full of flowers and just roam about there for an hour, obviously your music would be different, but then again, there is no real development going on. In other words, if you're thinking in terms of exposition-development-recap, always keep in mind that your development needs to lead somewhere. It shouldn't necessarily be a constant build-up of tension or an unendliche melodie, but it should have a purpose more concrete than 'developing thematic material'. Especially if you're working on a symphonic poem, you might want to prepare things which will happen much later on in the piece. You can foreshadow a lot without giving anything away, and this makes the actual material you are foreshadowing feel much more natural and relieving when it finally arrives. In the end, I think it has to do not so much with 'how am I going to fill another ten minutes with this material', but more with 'what can I do with this material that will be satisfying' or 'what does this material NEED in order to fully settle and become more than just a melody or a motif'. It's a question of experience, and writing lots and lots of music I guess, and looking at the masters in all shapes forms, and sizes, and seeing why they work their material in the way they do, and why it works. I'm sure you know the anecdote where someone asks Mozart how to write a symphony, and he answers, 'well, you have to study harmony and counterpoint and then write some rondos and whatnots, and then you can try your hand at a symphony'. The student remarks 'but you wrote your first symphony when you were ?9? (or whatever)!' and Mozart says 'yes, but I didn't have to ask anyone how to do it.' In other words, in order to write a large scale work, you must have had the experience of growing from a few bars to a page, to several pages, to a work of a few minutes, etc. etc. etc. Let me know how you're faring ;-) and much good luck.

-

It appears that Brandon has left us again... why? :)

-

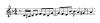

I would also like to put a subject up for grabs. I used it in a fugal episode in a string work last year, and would be interested to see what others do to it. If you don't like something about it, tell me why ;-).

-

Sorry, silly question, but what is the stepping tone? I've never heard that name be used for any scale degree... I just know them as tonic, supertonic, mediant, subdominant, dominant, submediant and leading note.